"Coronation" Mass by Mozart

Notes © Shulamit Hoffmann 2025

The Mass in C, KV 317, the "Coronation" Mass is the grandest and most popular of all Mozart's sacred works written in Salzburg; the Requiem and the C minor Mass being the two iconic sacred works from his Vienna period. In January 1779, Mozart returned to Salzburg, his hometown, after a disastrous eighteen-month European tour, during which he had not been able to secure a professional post; the love of his life, Aloysia Weber, had given him up for Josef Lange; and his mother had died while with him in Paris. As no other professional opportunity was forthcoming, Mozart took up a position in the service of the Archbishop of Salzburg. The instructions of his appointment were to "unbegrudgingly and with great diligence discharge his duties both in the cathedral and at court and in the chapel house, and as occasion presents, to provide the court and church with new compositions of his own creation."

At the first opportunity Mozart fulfilled this last demand by composing the "Coronation Mass." He dates his score "March 23, 1779," most likely the date of completion of the work, as was his habit, and it was probably performed for the Easter Day service on April 4, barely two weeks later. The celebratory nature of the music belies the personal disappointments that Mozart was harboring. Indeed, the piece is filled with aplomb and assurance.

Mozart himself described the task of writing a Mass in a letter: "Our church music is very different from that of Italy, all the more so since a mass with all its movements, even for the most solemn occasions when the sovereign himself reads the mass (e.g. Easter Day), must not last more than three quarters of an hour. One needs a special training for this type of composition, and it must also be a mass with all instruments—war trumpets, tympani etc."

Thus, Mozart was obliged to write in the form that was preferred by the Archbishop, a hybrid combination of the compact "Short Mass" and the instrumental grandeur of a "Solemn Mass"—horns, trumpets, and timpani. With the "Coronation Mass," Mozart's most splendid early sacred work, the young composer puts his best compositional foot forward to justify his new appointment. Not only is the music wonderful in and of itself, but the text setting and the music's capturing and reflecting both the literal meaning and the implied moods of the text is masterful.

Even as early as the nineteenth century, this Mass was already popularly referred to as the "Coronation Mass." The nickname at first grew out of the belief that Mozart had written the Mass for Salzburg's annual celebration of the crowning of the Shrine of the Virgin at the church of Maria Plain, just outside Salzburg, where a "miraculous" painting was installed. But recent scholarship suggests that certain dates do not support this theory.

The more likely explanation is that the Mass was one of the works performed during the coronation festivities in Prague, perhaps as early as August 1791 for Leopold II. Mozart had written from Prague requesting that the parts for his old Mass in C be sent to him there.

Another possibility is a posthumous performace, for Leopold's successor Francis I in August 1792. There is extant another set of parts dating from 1792 and the same parts were probably used the year before. Mozart had a more felicitous relationship with Prague than he did with Vienna, so it is not unlikely that a mass of his would be performed at a coronation ceremony in a city that so appreciated his music. in all probability, the moniker "Coronation" would have grown from there. Certainly, the music's resplendent pomp befits a coronation.

In Salzburg, the practice of mass performances for religious services included the interpolation, between the movements of the mass, not only of liturgical readings but of other short musical pieces. Under the "forty-five minutes and no more" constraints of the Archbishop, Mozart composed seventeen Church or Epistle Sonatas, each en miniature, to be inserted between Mass movements. We have adopted this practice and we have chosen Church Sonata KV 329 (317a)* to be performed between the Mass' Gloria and Credo sections. The sonata is in the same key as the "Coronation" Mass, fulsomely scored for the same instrumentation—somewhat unusual for Church music, and is thus almost certainly the one that Mozart wrote for the first performance of the

this Mass.

The Kyrie, the first movement of the Mass, opens in dignified splendor, winds and timpani punctuating the exclamations of the full chorus and the violins marching in processional, unison, dotted rhythms. With a slight shift to a more lyrical line, the soprano soloist enters, followed by the tenor, with an oboe tail-gaiting, commenting on the duet.

Opera buffs will recognize the soprano's exquisite opening phrase: more than a decade later, Mozart uses the same phrase and the same instrumental introduction, in Fiordiligi's aria, "Come scoglio" in Cosi fan Tutte. The chorus returns to close the movement with more of the majesty of the opening.

Salzburg Cathedral

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Mozart Shrine of the Virgin at Maria Plain

St Vitus Cathedralin Prague

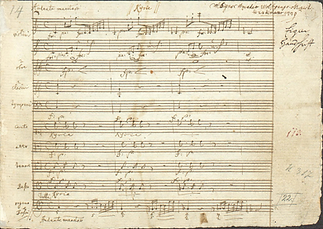

First page of the autograph manuscript of the Krönungsmesse (Coronation Mass)

The Gloria is set in sonata-allegro form, with exposition, development, and

recapitulation. It opens with ebullient joy as it expresses glory and praise of God and tenderness for "men of goodwill." In this movement, the choral statements offset the music of the four soloists, as gold or platinum settings of fine jewelry show off precious gems. There is angst and urgency in the minor key setting of "who takes away the sins of the world" and ineffable sweetness in "you alone are holy." Foregoing the customary fusty fugue, Mozart skids headlong into a closing "Amen" romp.

Now for the instrumental Epistle Sonata that we have already introduced: the piece revels in the trompetto figurations that the brass instrumentation so readily affords. Confident, ascending twirls, forteand piano, mark the first subject; the second subject, a polite discussion between strings and oboes. Mozart seems to be having such a jolly good time with strings, oboes, horns, trumpets, timpani, and organ at his command and the music unfurls exuberantly.

Back in the Mass, Mozart avoids the pitfalls of the wordy and rambling Credo text firstly by using rondo form, the recurring and reassuringly recognizable rondo subject being the music of Credo in unum Deum. Secondly, because of his virtuosic, fleet-footed setting of the text, we sing a lot of Latin in a short time! Not so easy for the chorus, mind you.

A nod of well-earned praise for the violinists, who tear through a veritable torrent of sixteenths in a style that has become known as the rauschende Violinen (rustling violins). And never was rustling more artful! After a lot of hustle and bustle the tempo slackens in the middle section for the soloists' poignant Et incarnatus est and the chorus' powerful Crucifixus. The rustling violins and the chorus return to close this, the longest and densest movement of the Mass, brilliantly, without a hint of academe and with a jubilant "Et resurrexit."

The Sanctus opens with the chorus en masse effectively conveying

the maestoso (majestic) injunction of the composer. But soon Mozart can contain his ebullience no longer, and the music breaks into a bubbling allegro gallop with shouts of "Hosanna in the highest."

The reflective mood of the Benedictus is set by the strings, in a dolce (sweet) melody that is taken over by the quartet of soloists and made into a full-bodied statement about "He who comes in the name of the Lord." But the chorus will not be left out: bursting with "Hosannas" (from the Sanctus) still to be sung, they are still full of musical beans. With a sudden shift to allegro, they interject more of these spirited, dance-like calls.

The orchestra eloquently introduces the finale, setting the stage of the Agnus Dei for the soprano soloist. Once again, Mozart, ever the opera composer, knows the potent affect and effect of his melody. This one he uses nine years later as the Countess Almaviva's aria Dove sono in The Marriage of Figaro. After the tear-inducing supernal aria, the music segues into the Dona nobis pacem.

Mozart returns to the first soprano aria of the Kyrie, setting dona nobis words to the Kyrie tune, not for any liturgical connection, but for sheer melodic beauty. This juxtaposition of two sublime arias is so rich musically and transcends the sacred-secular distinctions! After the soprano's solo the three other soloists join her for a final quartet fling. The chorus enters, enthusiastic to join the party, the tempo revs up a notch, and the finale canters home with hopeful, indeed, joyful, appeals for peace.

Click on the image above to watch